In the aftermath of the massive and seemingly never ending disruptions of the past few years, educational leaders are encountering new challenges in putting the pieces back together. McKinsey & Company recently shared some perspectives in an article titled COVID-19 and education: An emerging K-shaped recovery. In economics, a K-shaped recovery describes a post-recession scenario where some segments of the economy rebound quickly and thrive, while others struggle and stagnate. In education, McKinsey suggests the K-shaped recovery disproportionately impacts specific sectors—in this case, Black and other minority vs. white students. These disproportionate impacts have, of course, always existed and have been further fueled by economic disparities. But, according to McKinsey, the pandemic has heightened the gaps, putting Black and minority students further behind their white counterparts.

In a webinar on mitigating learning loss, Janice Case, California director of the National Center on Education and The Economy (NCEE), said that educators the pandemic created a moment of urgency around the fact that students have been falling behind for some time, requiring new reflection into the root causes new systems-level approaches how to meet students where they are.

The discrepancies are likely to continue as the country—and, in fact, the world—continues to deal with lingering impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic and, especially, the emergence of new variants like omicron.

Interestingly, amid the continued uncertainty, many families—particularly those in underserved environments—increasingly demand virtual alternatives to replace or supplement in-person classes. Virtual school models are well-positioned to help overcome the shortcomings of standard learning; more robust offerings are already proving more effective than some of the early attempts to deliver remote or virtual classes.

While, before the pandemic, research generally indicated that students attending virtual schools performed poorly compared to those learning in-person, that is no longer the case. Emerging evidence-based models for virtual learning now emphasize teaching quality, live classes with well-trained, district-based teachers, productive use of student time and attention, peer learning, technological capacity, and the effective use of data.

New opportunities are emerging to go beyond the typical setting (time, place, pace) and to set up learning structures to address the needs of students in varying ways.

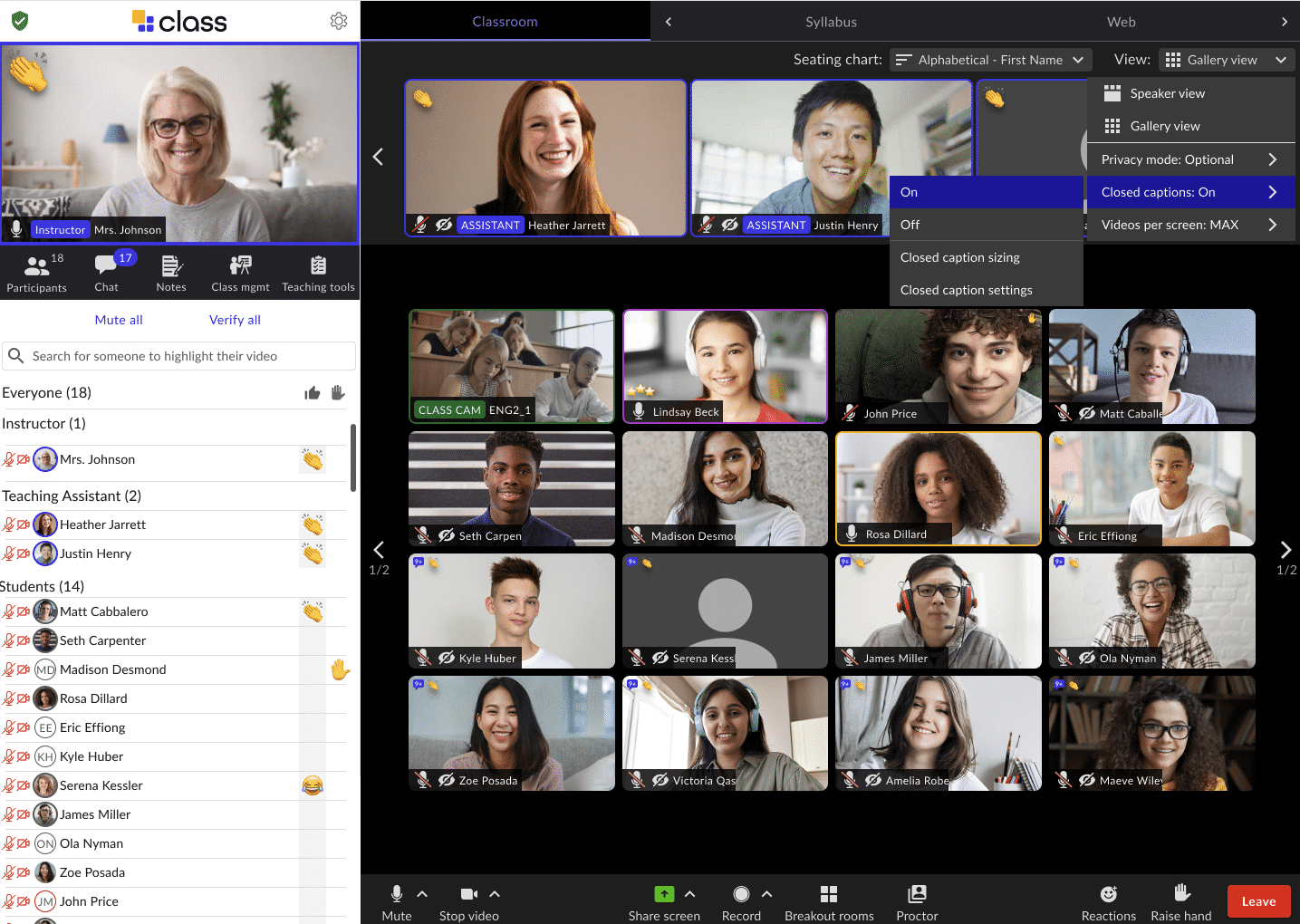

Administrators, teachers, students, and families were unexpectedly thrust into the remote learning environment with little to no time to prepare in early 2020. However, several months of these experiences and the increasing capabilities of classroom technologies led to widespread improvements and the emerging realization that virtual learning should no longer be considered a “lesser option” but a value-added alternative to education in traditional classrooms.

It’s essential to strategically approach virtual learning with input from a wide range of stakeholders—one of the critical considerations in achieving digital equity to impact that K-shaped recovery.

Virtual learning opens up new opportunities in redesign to better meet the varied needs of learners and leverage the creative competencies of instructors and administrators.

Jane Ferris, assistant head of school at Laurel Springs School, says: “Online learning provides students with opportunities to choose their path, time, place, and pace around their learning. Without school or scheduling constraints, students can create the academic path that best meets their interests and needs.”

Online learning allows students to choose when they work and learn best and accommodate personal and family scheduling needs. “When learning online, students can pace at a speed that is conducive to their academic needs,” Ferris says. “Since instructional materials are available for students at any time, students can access them, and review and relearn as they master skills and concepts.”

There are other significant benefits in scheduling and offering classes to meet niche needs, Brian Galvin, Chief Academic Officer at Varsity Tutors, points out. “When students don’t have to be grouped by geography—who’s in which building—schools can offer a much wider variety of elective topics and extracurricular activities,” he says. Traditionally, Galvin says, schools are often limited by the need to have a minimum threshold of students to justify a teacher and classroom. So they may be able to offer only one computer science class or one art class, etc.

“But online, when drawing from several schools or even across several districts, it’s easy to pool together a minimum number of students on a topic they’re truly passionate about or want to dive in deep,” Galvin says. “You can offer classes or clubs on video game creation and graphic design tools and unique programming languages as opposed to just one ‘computers’ class. Likewise, you can offer separate painting and drawing and animation classes and not just ‘art’.”

The pandemic experience with online education, Galvin says, demonstrates that while fully remote learning for all learners may not be the answer, “in the right doses, the ability to teach and learn online provides unprecedented learning opportunities that just didn’t work before.”

Of course, all of this potential is contingent on ensuring equal access—digital equity—for all.

In an article for EdSurge, Beth Holland, a partner at The Learning Accelerator, a nonprofit that connects teachers and leaders with resources to help transform K-12 education, shared some suggestions for schools and school districts as they consider ways to impact digital equity positively. She made the point that every school, and every district, will take different approaches and that an iterative process will be necessary, and recommended the following steps:

It’s time to begin, renew, or expand discussions around opportunities for redesign, leveraging the vast array of technological options and aids now available, and think about innovative ways to make these opportunities accessible for all.

Download the eBook, The Future Is Virtual: 5 Considerations for Launching a Virtual Academy in Your School District, for practical advice on how to create new opportunities for virtual learning.

Get our insights, tips, and best practices delivered to your inbox

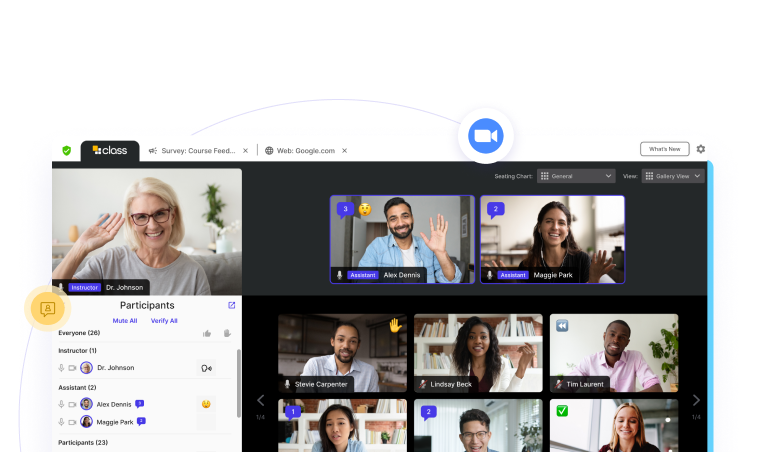

Sign up for a product demo today to learn how Class’s virtual classroom powers digital transformation at your organization.

Features

Products

Integrations